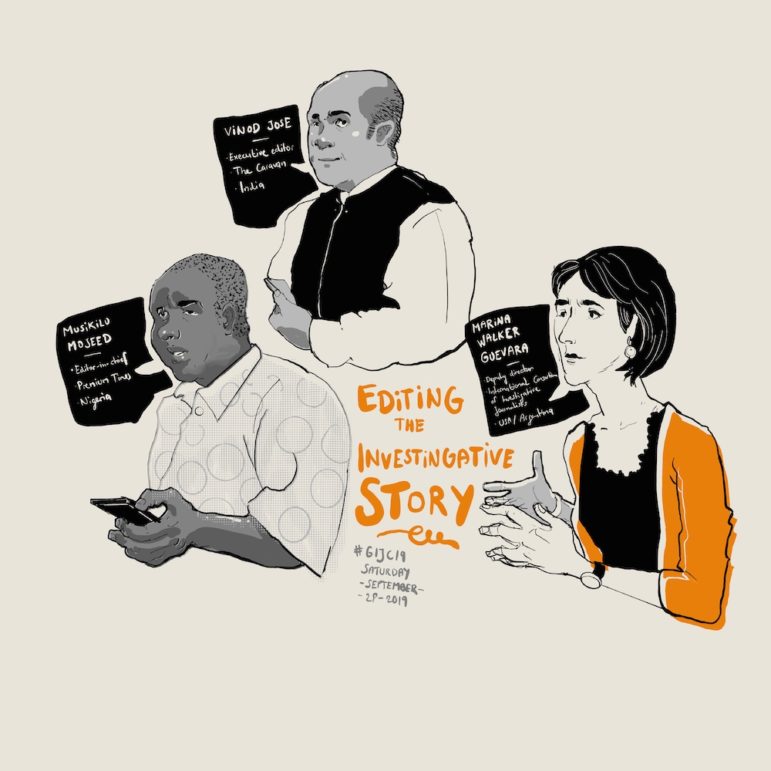

Illustration: Phil Ninh

Great editing begins with story conception and continues through the reporting process, all the way to the final project. At the “Editing the Investigative Story” panel held during the 11th Global Investigative Journalism Conference, three editors shared their tips and tools for how to bring a story from conception to realization, and how to ensure an investigation has both bullet-proof reporting and an artfully-crafted narrative.

Good Editing Choices Begin at the Beginning

Marina Walker Guevara, director of Strategic Initiatives and Network at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, managed the two largest collaborations of reporters in journalism history: the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers.

When a story proposal arrives on Walker Guevara’s desk at the ICIJ, she asks herself a series of questions before deciding whether or not to commission it: Is this an issue of global concern? Are the systems designed to protect people broken? Are we likely to get a result? Does this involve powerful institutions? Who are the victims? Are there powerful forces trying to hide the truth?

While some of these questions may be specific to the ICIJ, Walker Guevara says that all editors need to decide what stories to prioritize depending on their individual mission and the community they serve.

“With an investigation, we are going to be investing so much time and so many resources that are precious so it is very important to have criteria,” she said.

She also emphasized that investigations don’t always have to focus on illegal activities. When her team started looking into the Panama Papers, a lot of the financial dealings were framed as perfectly legal.

“Just because powerful elites have sanctioned doesn’t make it any less newsworthy, urgent, and important,” she said. “They are often outrageous and immoral issues. As a professor of mine said, ‘Slavery was legal for so long.’”

Be a Coach

Once the reporting has started, Walker Guevara likens editing to coaching.

“A coach in the sense of someone who has been in the field many, many times, hopefully as a player, who has had many wins and losses and all kinds of experiences and who is now taking a step back to help develop others and get the best out of his reporters,” Walker Guevara said. “They should be able to make tough calls for the team and the investigation.”

Part of that means keeping the team organized and on track during the many months of an investigation. Walker Guevara says editors should work with their journalists to build timelines, map information, and write frequent memos.

“They don’t need to be three pages,” she said. “It just means having the discipline to write a few paragraphs to your editor saying, this is what I accomplished, this is what I am missing and this is my goal for next week.”

When it comes to editing, Walker Guevara says editors should strive for writing that is clear and engaging, no matter how complex the details are.

“Your grandmother needs to be able to understand it,” Walker Guevara said.

Perhaps most importantly, an editor must ensure that the story is bulletproof. That involves giving subjects fair opportunity for comment before publication. While the story is being drafted, Walker Guevara recommends footnoting all the facts. She also says it is a good idea to bring in a fact-checker.

Even when the investigation is completed, fact-checked, and ready for publication, Walker Guevara recommended a final step. An editor she once worked with organized what he called “confession time.” He’d sit down with a reporter and ask them to be honest about whether they were losing sleep over anything in the investigation or if they had any lingering doubts about even the smallest aspect. “There has to be a lot of trust between reporter and coach for this to work,” she said. “But there is always something to fix.”

Editing for Narrative

Vinod K. Jose is the Executive Editor of The Caravan, India’s premier magazine for narrative and investigative journalism.

Jose agrees with Walker Guevara that good editing starts at the very beginning of the process — with crafting the very idea for a piece. It’s important to establish a hypothesis and keep that goal in mind. This is important, as Jose says many journalists at The Caravan might work on a story for months or even years.

“The longer you work on it, the more likely you are to become lost,” he said.

Comparing an investigation to a boat, Jose said the editor has to be the rudder, making sure that the reporter doesn’t lose sight of the shore.

Storytelling is an important part of The Caravan’s investigative journalism. According to Jose, the investigative stories that he publishes “are crafted into dramatic narratives that employ pace, color, character, and literary style.” Though the articles are meticulously researched and factually accurate, he says they should read like great fiction.

To that end, Jose gets his reporters to apply feature reporting skills to their investigations. He says he tells them to look for “scene setting elements (landscapes, textures, colors, emotions), characters, dialogue, interactions, pacing, structure and detail.”

That said, you should never let the pursuit of narrative surpass investigative instincts.

“You should have your bullshit detector on at all times,” Jose said.

Always Remain Skeptical

When Musikilu Mojeed, editor-in-chief of Nigeria’s Premium Times, edits a story, he makes sure he has done his homework.

“You need to read up like your reporter,” Mojeed said. “Editors must ensure they have deep knowledge of what is being investigated.”

He and his team shared a Pulitzer with other ICIJ journalists for their groundbreaking reporting on the Panama Papers.

However, Mojeed’s biggest tip is that “editors must be really, really skeptical” — even when you are dealing with your No. 1 reporter.

Mojeed may never let his reporters off easy, but he also says it is an editor’s job to make sure they are safe. “Online, digital, and physical security are key,” he said. “Plan for them.”

But the story isn’t over when the text hits the page, or the screen.

“You must plan for post-publication backlash or danger,” he said. “If the reporter must get out of town before publication, make sure that happens. If we think the reporter will come under online attack, you must prepare him for what is to come.”

Brenna Daldorph is a freelance audio producer and journalist, based in London, after growing up in Kansas and spending many years in Paris. She often works for PRI’s The World and The Guardian. Many of her stories focus on trauma and resilience among children and young people. In the past few years, she’s reported from Kenya, the Central African Republic, and Nigeria. More than anything else, she has a penchant for stories about people.